.jpg)

In June 2000 we bought Lifeline R, a 49' cray fishing boat from King Island in Bass Strait. Known for rough seas and tough conditions, Bass Strait is the narrow stretch of water between the Australian mainland and its southernmost state of Tasmania. It separates the Tasman Sea in the east and the Indian Ocean in the west.

Lifeline was purchased after six months of boatlessness. After thousands of kilometres of fruitless searching for a seaworthy passagemaker capable of South East Asian cruising about 43 - 45 feet long...

In December 1999 we'd sold Tantivy, our 36 ft varnished sided ex-game fishing boat. We'd owned Tantivy for nine years and cruised the Queensland coast for two years. We'd planned our replacement and we wanted it now!

We didn't really set out to convert a workboat. It just happened. We couldn't buy the boat we wanted. It had to be full displacement, seaworthy, economical to run, with human scale amenities and room to give ourselves and guests privacy without allotting permanent guest accommodation which would be used only occasionally. Fishing boats were available. Bass Strait boats were proven. We believed we could convert one for an all up finished cost of $(AUD)150,000 (Ha! We ended up spending more than that on the conversion alone). We decided this was the only way we would get the boat we needed for the money we could afford.

Armed with the caution from the shipwright who had built and worked on Tantivy, not to buy anything older than thirty years, we took the plunge.

Lifeline R had been built by Barlow shipbuilders in Ballina, New South Wales, Australia in 1971, starting life as a prawn trawler. She's 48 or 49 feet long (depending how you measure her), 14 feet 6 inches in beam with 6 feet of draft. Heavy displacement, she weighs 32 tonnes. Her hull is a sharpie design with hardwood frame and planks (we believe a mixture of spotted gum and ironbark).

Powered by a Gardner 6LX, coupled with a 38inch propellor, Lifeline gets along at a cruising speed of about 7.0 knots for 1100 RPM. We believe that diesel usage will be 10 litres per hour at those revs but are also hopeful of better economy by changing the pitch of the prop. (We are yet to definitively work out the fuel usage. When Philip brought the boat to Queensland from Southern Victoria he motored at 9 knots, 1300 RPM using 14 litres per hour. However the boat was dragging 32 holes in her bottom for the wet well). More on fuel economy to come....[****15 Sep. 2002: After cruising the boat for twelve months we are consistently getting 7 - 8 litres per hour at 7 knots (1100 RPM) and we are ecstatic!!****]

This is what Lifeline looked like when we bought her.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Lifeline came with lots of gear which we kept and some which we sold or discarded. As well as the hull, deck and engine, hydraulic steering lines, we kept the 80lbs anchor and 90 metres of half inch chain, hydraulic anchor winch, 2 x 800 litre fuel tanks, arms and solid stainless paravanes, safety gear (including liferaft, EPIRB, good quality lifejackets etc) fairly new electronics (including radar, GPS and plotter, sounders, HF and VHF radios), keel cooling and dry exhaust, lots of ropes of the right size, assorted pumps, gauges, steering wheel, stainless cooking stove etc. When looking at work boats to convert, the age of the gear is a significant factor in the value of the proposition. Much of Lifeline's gear had been put on the boat by the most recent owner within the last 4 years. Because she was in survey, safety gear etc had been kept up to date.

Good gear we didn't use included a 14 KVA Kohler generator less than 4 years old. (We hate generators and installed solar panels instead), a large refrigeration plant (we used some of the 5 inch thick insulation from the freezer room, though, when building the box for our 24 volt DC fridge/freezer), 240 volt flood lights, satellite phone, UHF CB radio, marine toilet (we installed a household toilet at deck level).

The Plan

In selling Tantivy and buying a new boat we aimed to achieve the following 3 primary objectives:

1) Greater seaworthiness through: deeper draft, lower profile hull and superstructure; less window area exposed to the sea;

2)Greater range (2,500 miles) through a combination of single engine rather than twins, fuel economy of the engine and larger fuel tanks;

3)Comfortable permanent liveaboard homeliness including house sized amenities, private space for guests and good storage capacity, water capacity etc.

An unspoken definite fourth objective, though, was a seakindly motion and the flopper stoppers won Philip's heart on the thousand mile delivery journey up to Queensland.

We also wanted to keep our living costs to a minimum, so designed the boat to be able to stay out of port and away from marinas comfortably. Heavy displacement and flopperstoppers would help the motion in marginal anchorages but we also determined to have a robust tender with a large outboard for covering distance.

Our Lifeline was to be a boat to be lived on and cruised. Not a glamour boat. We would fish from the cockpit and sit on her lounges in our wet swimming togs. And spill red wine on the floor when we copped a wake from a passing Riviera.

What We Did

The conversion project was carried out by a qualified boatbuilder in Queensland. Although the boat came from Tasmania and we were living between Sydney and Canberra at the time, we chose to build in Queensland largely because of the boatbuilder. First, he had completed several conversions of work boats to pleasure boats and was able to show us his work and introduce us to the owners. Second, he demonstrated a willingness and capability to problem solve, to create systems and use parts from the boat but with a passion for strength and using the best. Third, his hourly rates were very competitive when compared with the going rates for boatbuilders in Sydney. Fourth, he was able to secure a primitive but private berth in a creek off the main Brisbane River cheaply. And fifth, we liked and trusted him.

He advised that the project would take "about six months" to convert the boat "to workboat standard". (I never really worked out what "workboat" standard was because the boats he'd shown us were luxurious and the boat we now have far exceeds our expectations and took more than twice that time to convert).

The project began in July 2000 with the boatbuilder taking Lifeline up on the slip to fill the holes in the wet well and check out her undersides. We deposited $A10,000 into his account and he purchased materials and debited his wages against it. At the end of every month for the life of the project he would present us with a statement of his hours and costs and we would deposit money from time to time into his account.

The Boatbuilder

At this point it is appropriate to talk about our boatbuilder. We didn't know it then, but we do now, that the "warm and fuzzy" aspects of working with a boatbuilder are at least as important as the strictly skill, business and financial ones. After all, you will have a relationship with this person for at least six months (or in our case twelve). And there are so many thousands of decisions to be made in custom converting a boat and you can't be there for every one of them. Trust in both directions is very important. As is understanding intimately the requirements of the project. And being flexible in your layout.

We had some fun early on when we presented the boatbuilder with our plans drawn to scale, the result of months of discussions, sketches, poring over designs, more discussions, whiteout, photocopying and more sketching..... He never works from plans. The design just "evolves". Sometimes things "just fit". Other times they don't. Early on that made me just a little nervous. What had we got ourselves into here? Were we going to end up with the boatbuilder's design, not ours?

Our first example of things not fitting when you try them in real life (not on paper plans) was the galley, which I'd planned as a U-shape opposite the dinette up forward. When drawing our plans we hadn't allowed for the thickness of the walls. So the cabin was almost a foot narrower than we'd thought. (The boatbuilder had also made the decks wider than we anticipated, again decreasing the cabin width). To ensure a feeling of spaciousness we had already determined that all interior walkways had to be at least 3 feet wide.

So the galley went amidships and was no longer a U-shape. The space it was originally scheduled to go became the top opening fridge and freezer under the nav. table. (How did I ever think I would fit a galley in there?)

The boatbuilder's way of doing things was proved right over and over again. The position of the exhaust determined the length of the dinette and the space for the gas hot water heater; the forward bulkhead influenced the shape of the stairs down to the forward stateroom etc etc etc. We worked from a layout, but that layout evolved and so did our ideas of what we wanted.

Although he had fitted out many barges and workboats, our boatbuilder's experience with pleasure boats was essentially with day boats. Boats that might go to the Great Barrier Reef for three months but which would always return to their berths to have attention lavished on them by their well heeled owners. He couldn't quite understand the different needs of a cruising powerboat that was to be lived on permanently on a shoestring budget and with no fixed address. For example, in many parts of Queensland, water is unavailable in large quantities except on a marina so being able to catch and store plenty of water was important to us; as we have no other living address, having enough storage to keep all our "stuff" (such as the boxes of dress ups, the "work clothes" ...just in case..., the tennis racquets, bikes, boogie board etc) as well as lots of boat gear.

He also had no concept of the power passagemaker, still an emerging type in Australia. We set out to give him some background to the Beebe philosophy of "crossing oceans in your carpet slippers" and some of the design considerations we thought were important.

What We Did

First, anything above deck that could be re-used was removed and stored. This included things like the electronics, barometer, stove, steering wheel etc. But Philip and I also spent time unscrewing stainless steel screws, bolts etc. This went nowhere near supplying the number of fastenings needed but did save a bit of money. Fastenings were a major cost!

Work began below deck. The foc'sle was gutted, the generator removed, the existing 1600 litre fuel tanks moved aft out of the engine room and two extra tanks fitted (another 1500 litres). As Lifeline had only a small flexible water tank, two stainless water tanks holding 1500 litres were installed, along with a 500 litre holding tank. The wet well and freezer were demolished and a bulkhead constructed aft. The hull now had four bulkheads dividing it into five distinct spaces. Moving aft, these were anchor well, forward cabin, engine room, tank room (also known as "pantry") and lazarette (also known as "junk room").

As Lifeline used hydraulics for pot hauling, which we didn't need, the hydraulic lines had to be reengineered. New fuel and water lines were installed.

Meanwhile the underfloor areas were cleaned and painted - Philip's job. Thirty years of accumulated bilge blecchhh, soot, grease, salt water, flakey paint inhabiting hundreds of nooks and crannies created by the frames, stringers and planks of the hull had to be scrubbed with turps, vaccuumed and painted. No point in paying a professional to do the labouring work so Philip and I got those jobs. Well, Philip mainly. He was on site nearly full time while I was still dividing my time between Sydney and Canberra. But I can't count the number of bins we emptied or the number of times we vaccuumed up wood shavings over the life of the project!

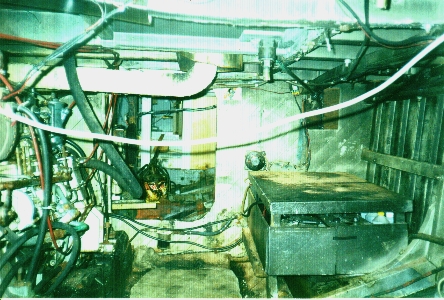

A view of the engine room after washing the walls with turps but before painting!

Lifeline's deckhouse was completely demolished after building the new one around it. We realised just how strong the old one was as the boatbuilder sledgehammered it away. Floor to ceiling bolts held it rigid to the deck.

Construction of the new deckhouse was similar to building a very strong house frame. A treated pine frame was bolted to 6"x2" timbers bolted to the deck beams which formed the curve of the walls.

Framing for the

Topsides.

Framing for the

Topsides.

This was then covered on the outside with half inch structural ply, Everdured (epoxy saturated) and the whole was fibreglassed. Eventually this was two pack painted.

While the deckhouse went up rapidly, the fitout and finishing seemed to take forever. Again the shipwright was on the mark when he warned us that it seems like the job is nearly finished when the deckhouse walls are up, but there is still a long way to go.

We started to firm up our measurements for furniture and fitout. We knew we wanted the dinette to drop down to make a berth so it had to be at least 1.9 metres long. We wanted a queen size island bed in the forecabin and enough room to move, so the size of the cupboards and wardrobes was determined. As we live and cruise in a sunny climate, we had to have a large covered cockpit/aft deck.

We started holding up sheets of plywood as "walls" trying out the spaces we had designed for size. Was "this size bathroom" big enough to get dressed in? If we put a wall here would there be enough room to walk past?

We wanted Lifeline to have a spacious open feel, while having a deck level bathroom in the middle of the boat. A challenge but we think we have succeeded.

Lifeline has just one permanent stateroom but a loungeroom/office that can be closed off from the rest of the boat, with a sofa that converts to a queen size double bed. For the 90% of the time that we don't have guests we use it as a wonderful spacious and comfortable lounging area that opens onto our terrace (the cockpit). Interior finishes are a combination of mahogany, laminates and painted surfaces. (We wanted to be able to change the colour scheme from time to time - Wattyl I.D. water based paint is durable, scrubbable and easily painted over.)

Looking Forward: Saloon, Galley, Helmstation

Lifeline has a Gardner 6LX 120 hp engine. A Gardner is a large capacity, slow revving, heavy duty, high torque diesel. Gardners live forever. Before we bought Lifeline, Philip had hoped we would get a Gardner with our next boat.

Getting someone to service our Gardner, however, was a different story. The experts are much in demand. Our mechanic would disassemble and take away parts of the engine and then not re-appear for weeks. The service took place over several months and included servicing the oil coolers and freshwater keel cooling system, new bellows in the exhaust system, adjusting the governor, setting up duel fuel filters, new fuel lines, new v-belts changing the oil and filters etc.

Our good friend Leon, (far more than an electrical genius and ex-boatie), gave us a safe, robust, clever system that even a techno-cretin like me can operate. In a nutshell, the electronics are mostly 12 volt, lights in the bathroom, driving station and outside are mostly 24 volt, as are the fridge and the party lights plug in the cockpit, and interior lights and equipment are mostly 240 volt. We have an impressive switchboard and diagrams of our whole system.

Lifeline was completely re-wired for 12 volt, 24 volt and 240 volt through an 800 watt inverter. As we hate generators, power for the system (including our 24 volt fridge and freezer) is generated from four 80 watt solar panels on the upper deck. We also retained two 60 watt solar panels to charge the emergency battery bank.

[NOTE: 15 Sep. 2002: We have sat for as long as a month without having to turn on an engine. Our solar panels meet all our electricity needs.]

One big advantage of going through an inverter is that we could use household fittings and appliances, which meant we had far more choice than if we had had to use marine fittings. This in turn meant we could choose low wattage flouros but without having to have nasty flouro white light glare. (Low wattage flourescent globes in lamps and light fittings can provide soft warm light and can be bought in lower wattages than halogens - we use mostly 5 watt globes. Low wattages allow for low battery drain.) And we were able to buy our fittings etc more economically. Another advantage we have realised as we have spent more time on marinas than we thought we would, is that the boat converts to shore power at the flick of a switch.

While I'm talking about low battery drain....One more clever thing Leon did was build us an LED anchor light. This marvellous invention draws almost no power and so we use it every night (and sometimes during the day when we forget to turn it off.)

Our 24 volt fridge/freezer is small by many powerboat standards these days. It is also a "chest" style (top opening) rather than an upright with a front opening door. And when closed, becomes the chart table - just like in countless yachts. The freezer is 35 litres capacity and the fridge is 120 litres. Each has a separate insulated lid. (As previously mentioned, we re-used some of the insulation from Lifeline's freezer room and so have 5" of insulation around each of the fridge and freezer spaces.) We have a plastic coated wire basket in the top of the fridge which can be lifted out to get to the stuff on the bottom. This can be a bit of a pain at times - but not nearly as much as having to be a slave to a motor/generator-driven eutectic freezer!

Despite its size, we are able to store enough fresh provisions and meat for two people for a month. With that amount of food it is chockers and Philip has real trouble finding space for his 2 can daily beer ration.

The system was built by Moorebank Refrigeration in Sydney and uses a Danfoss compressor with a U-shaped plate in the freezer. Holes in the wall between the freezer and the fridge allow leakage of cold from the freezer to the fridge. It's that simple. The freezer stays between -4 and -7 degrees at ambient temperatures in the twenties (degrees centigrade). Under normal operation at 24 volts it uses 1.8 amps when cycling on and it cycles 20 minutes on and twenty minutes off. Less than 22 amps in 24 hours! Sometimes when we first stock the fridge and freezer we run the unit on its maximum setting, for 24 hours , which uses 3 amps when cycling.

Gas fitting was carried out by a licensed gasfitter. We have a (LPG) storage locker (portside aft) with drains which holds a 9 kg gas bottle. This feeds a barbecue in the cockpit, the stove in the galley and the instant hot water service (in another ventilated locker portside). With just the two of us on board living at anchor this lasts us exactly one month. NOTE: March 2005. If we turn the gas hot water off, cylinders last more than two months.

Household fittings and pipes were also used for the plumbing of water and sewage. Because the bathroom is above the waterline, we fitted a press button household toilet with concealed cistern in the wall cavity. After flushing, the cistern is refilled by a salt water pump. Because of the way refilling the cistern is regulated by a float switch, Philip found we needed an accumulator tank to stop the pump switching itself on and off. This he built to Leon's design (yes, Leon is multi talented) using 4" conduit reinforced at the ends.

One of the last exterior jobs we did before painting the hull and decks was to have 2" section polished 316 stainless steel pipe welded to the original stanchions to form the handrails and pulpit. We kept the huge stainless steel bollards in each of the back corners of the cockpit and the stainless transom corner reinforcement.

The (Almost) Finished Boat (March 2001)

Since this photo was taken, we have put all the aerials, mast, radar and stainless steel crane on the roof. The hull has also been painted, the boat detailed and the rigging for the stabiliser arms has been added.

I imagine there comes a time in the life of every boatbuilding project when you begin to believe you will never finish. For that matter, what is "finished"? We bid farewell to the boatbuilder when the interior furniture and trim looked finished and the boat could move under her own power. That was midway through July 2001, a year after he started work.

Since then we've painted and varnished throughout, had carpets fitted, made curtains for all windows and completed all the upholstery, put shelves in the cupboards, in the tank room, and made bookshelves and spice racks. We've laid cockpit carpet and painted the hull and decks. Plus LOTS of industrial cleaning and detailing. After twelve months of woodwork, fibreglassing, epoxying, grinding etc etc, you can imagine how many blobs of junk were stuck to parts all over the boat (we're still scraping them off.)

Like everyone tells you, it always costs a lot more to do a boat than you think it will. (Some say double and others triple what you expect). In our case this came about partially because we didn't know enough about the process to know how to control costs (and that wasn't our boatbuilder's strength) and also because as we went along we chose more expensive options. The thinking goes something like this:

"Do you want laminate or mahogany?"

"How much difference is there in price?"

"They both need about the same amount of labour so maybe $1500 extra for timber."

"Do it in mahogany. Everything else has been done so well, it is silly to quibble over $1500 when you look at the total cost."

But all the extra $1500s add up. Yes, we paid more for our boat than we hoped. But we have a far better boat than we expected (and we believe if we had to sell Lifeline tomorrow we would probably get back what we paid.)

The Result

Lifeline is our one bedroom apartment on water. Unlike a houseboat though, she can go seriously to sea. She sleeps two permanently, can sleep two occasional guests in a convertible queen size double, and it is also possible to convert the dinette for one and a half people. We have a large cockpit which we walk out to through the back door. And because all accommodation, apart from the forward stateroom, is at deck level we have all-on-one-level open plan living areas above and huge amounts of storage below. This is despite having tanks for 3,000 litres of diesel, 1,500 litres of water, 500 litres of waste and lots of space in the engine room. Yet the boat is still a manageable size for two people. Yes, we're pretty happy with her.

Finished Interior Cockpit